When Uruguay’s historic marijuana regulation law passed the Senate in December, it was a major victory for drug policy reform in Uruguay and around the world. To many analysts, the hard part appeared to be over. Though it took some arm-twisting in the lower house, the ruling Broad Front (Frente Amplio) coalition had managed to pass the bill and the likely next president, ex-President Tabare Vazquez, had endorsed it as well.

Even on the public opinion front, there was some room for optimism. Leading local pollster Cifra had released a survey in September 2013 which showed that opposition to marijuana legalization had fallen to 61 percent, a five-point drop since it was first proposed by President Jose Mujica in July 2012. And for the first time, Cifra found that the number of Broad Front voters who supported the measure was larger than those against it.

The Broad Front also looked well-positioned ahead of the October 2014 general election, and Vazquez’s return to office seemed inevitable. With an approval rating at 62 percent, Vazquez was the most popular politician in Uruguay, according to an August 2013 poll.

However, this rosy outlook has turned bleaker in recent months. As the October 26 vote draws nearer, Vazquez’s support has dropped, and it has become increasingly clear that the future of the marijuana regulation law (at least as it was passed) could be in jeopardy.

Public Opinion: Firmly Opposed

Last year’s slight dip in opposition to the law appears to have been temporary. While the gains among Broad Front voters have proven to be lasting, a July 2014 Cifra poll found that 64 percent of the general population remains against the law, the exact percentage found in a December 2012 poll by the same pollster.

Unfortunately, the dedicated efforts of the civil society Responsible Regulation (Regulacion Responsable) campaign appear to have had limited impact. A Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) survey released in June asked respondents about their attitudes towards the new law. The poll found opposition to be less than Cifra’s figure (59.9 percent), but more significantly, it pointed to a wide variation in perceptions of the official reasoning behind the measure.

Despite the fact that the issue has dominated local headlines since late 2012, 18.5 percent of Uruguayans said they did not know why the government was moving to regulate the black market for marijuana. And even though Responsible Regulation and others have been organizing forums and running an extensive public awareness campaign to flesh out the government’s discourse on the issue, the largest bloc of respondents — 37 percent — said they believe that the goal of the law is to prevent crime and combat drug trafficking, which is the narrative most commonly put forward by the Mujica administration.

SEE ALSO: Uruguay: Marijuana, Organized Crime, and the Politics of Drugs

The other two main arguments used by the Responsible Regulation campaign — that the law will address an existing social reality that is currently unchecked, and that it will improve public health by increasing access to medicinal marijuana and reducing users’ exposure to more harmful drugs — did not appear to register. Just 10 percent said they believed the law aimed to address an existing reality, and 6.6 percent said health reasons were the motive for its passage.

Meanwhile, 10 percent believed the marijuana regulation law was passed to bring in money, 5.5 percent said it was an attempt to get an electoral boost, and 12.3 percent gave other responses, which according to El Pais included that the law is “due to other interests and that it seeks to distract people from real problems.”

Fortunately, the law has not emerged as a major campaign issue ahead of the election. Instead, marijuana has largely taken a back seat to other hot button issues, like public education, the economy and rising insecurity.

The Broad Front’s Majority in Doubt

In the months leading up to Uruguay’s June primary elections, Vazquez’s own nomination was never in doubt. But the internal campaigns in the opposition Colorado and National parties appears to have had an energizing effect on the electorate. Perhaps due to the increased exposure given to fresh alternatives, Vazquez is no longer a shoo-in.

If Vazquez does not win an absolute majority on October 26, a runoff election will take place on November 30. For the Broad Front candidate, the poll numbers for a potential runoff are troubling. Coming out of the primaries, National Party nominee Luis Lacalle Pou has emerged as a serious challenger.

Some of this is due to dissatisfaction with the Broad Front’s performance on education and insecurity, but Lacalle Pou also deserves credit for organizing an optimistic and inclusive campaign that emphasizes his youthfulness and rejects political polarization. His campaign slogan is “for the positive,” and a slick campaign ad encourages voters not to “think it’s all bad” but to advance by “rescuing what is good.”

SEE ALSO: Uruguay News and Country Profile

According to pollster Factum, support for Vazquez has been falling in recent months, while support for Lacalle Pou has been growing. In a February survey of voters’ preferences in a hypothetical second round matchup, Factum found 59 percent support for Vazquez, and 34 percent for Lacalle Pou. In April these numbers were at 55 and 40 percent, and Factum’s July poll shows this trend continued, with 51 percent for Vazquez and 46 percent for Lacalle Pou.

What’s more, polls show that the Broad Front will likely lose its slim control of both houses of Congress. A Cifra survey released in August showed that voter intentions for the Broad Front were at 41 percent, the lowest level of support the pollster has found for the ruling coalition since 2012. By contrast, the National Party ‘s support hangs at 32 percent, and Cifra found 15 percent support for the Colorado Party and 4 percent for the Independent Party. If these numbers hold on election day, the Broad Front will lose its control in the House and Senate.

The loss of a congressional majority is the biggest potential threat to the law, because with an absolute majority the opposition could theoretically repeal the law altogether. But the outright dismantlement of the law is unlikely, especially considering that a number of lawmakers from the Colorado, National and smaller Independent parties supported sections of it in article-by-article votes in both houses. A more likely scenario would be the removal of some of the more controversial provisions like commercial sales and cannabis clubs, leaving the home cultivation of up to six plants for personal use.

Lacalle Pou’s Stance on Marijuana

To a lesser extent, Lacalle Pou’s surge is also a threat to the law, as his National Party has consistently been the largest bloc of critics of marijuana regulation. On July 26, he and his running mate (and former rival for the party’s presidential nomination) Jorge Larrañaga launched a joint platform, which among other things called for “the repeal of Law 19,178 legalizing the production, distribution and sale of marijuana by the State.”

But Lacalle Pou’s position on pot is more nuanced than most of his party, and especially than his vice president pick. While Larrañaga has consistently opposed marijuana legalization, Lacalle Pou is something of a maverick on the issue. In November 2010, he became the very first lawmaker to present a bill to legalize cultivation of marijuana for personal consumption.

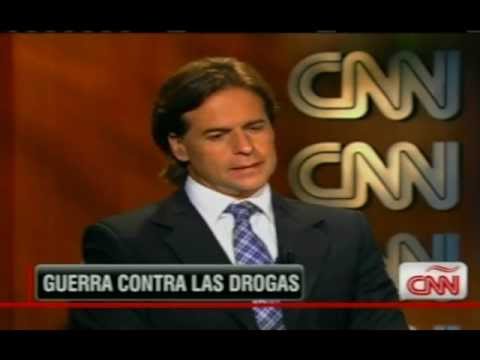

| In this 2011 CNN interview, Lacalle Pou defends his “autocultivo” bill. |

Lacalle Pou’s 2010 bill was surprisingly liberal considering it came from a leading figure in a party that leans conservative on social issues; it did not specify a limit on the number of cannabis plants one could have in the home, nor could any limit on how much marijuana was considered intended for “personal use.” However, it outlined strict penalties for any kind of sale of marijuana and other drugs, and proposed raising the mandatory minimum sentence for drug offenses to two years, without any possibility of alternative sentencing. In the end, Lacalle Pou’s initiative failed to get necessary support and was scrapped.

Fortunately for drug policy reform advocates, Lacalle Pou appears to be sticking to the spirit of his 2010 proposal. In remarks to reporters on August 21, Lacalle Pou confirmed his support for personal cultivation, but not for establishing a regulated market. The law, he said, “will end up only as personal cultivation […] It is a law where the state has abandoned its role of protecting public health.”

The Bottom Line

While Uruguayan public opinion remains staunchly opposed to marijuana regulation, it has not become a major campaign issue. Instead, the main risk to the law in the short term is the election and the Broad Front’s likely loss of congressional control. While the complete repeal of the law is improbable, some concessions to the opposition appear likely, and there is a chance the law could end up stripped of its most controversial elements, like the commercial sale in pharmacies and the cannabis clubs.

Ultimately, much of the law’s future will depend on the next president, especially with so much of its specifics outlined in executive regulations. Tabare Vazquez remains the leading candidate by a hair, but the race is now close enough that it is a good idea for drug policy advocates to get closer to Lacalle Pou’s campaign and figure out exactly where he stands. This author, at least, hopes to do so.

This post was originally written for an e-mail list of policy experts interested in tracking the politics of marijuana reform in Uruguay.

Geoffrey Ramsey is a part-time researcher for the Open Society Foundation’s Latin America Program and a freelance writer. Any views or opinions expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author.